There are numerous rules and conventions when it comes to writing fiction, and the lines between the two are often blurred.

There are numerous rules and conventions when it comes to writing fiction, and the lines between the two are often blurred.

Because writing is an art form, even fundamental rules about the form can be open to interpretation or debate. It can be a particular hazard for the novice writer, but even experienced writers can find themselves questioning rules and conventions.

Knowing whether to bend, break, or adhere to them is rarely straightforward, illustrating the complexity of an art form that has evolved over centuries and is still evolving today. Add in confounding factors like genre – each with its own conventions – and knowing what rules to bend or break in any given situation can seem daunting indeed. Added to this, conventions are different for different forms: screenwriting has different conventions to novels or novellas. Some examples may help add clarity to a complex topic.

Raise the Stakes

While it takes many different ingredients to craft an absorbing story, one of the most important is for there to be something at stake. The reader needs to feel that there’s a reason to keep turning pages and that the characters have something to gain, something to lose, and often both.

Consider a story where a man’s caught in a storm at sea on his little sailboat. The source of tension is pretty clear, and the stakes obvious: drowning’s a real possibility. But if we swap the sailboat for a passenger vessel, the stakes are that much higher. Throw in an active volcano on the horizon and you’ve got the ingredients for some high stakes drama. Raising the stakes is sound writing advice, but you can probably think of a novel where the stakes aren’t so high, but the story still sparkles. So when do we not raise the stakes?

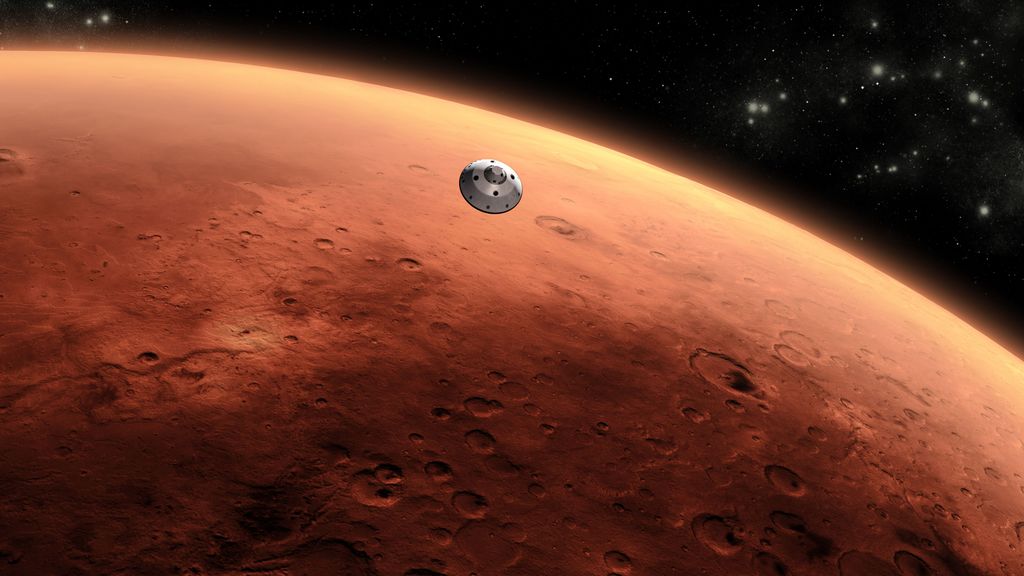

One good example of this is Andy Weir’s Science Fiction novel The Martian, later adapted into a blockbuster film. At the beginning of the novel, the protagonist is left behind, stranded on Mars and presumed dead by his crew. Trying to survive in a harsh environment in the hope of somehow escaping are the stakes for the protagonist, but the stakes could have been raised even higher. What if more than one person had been left behind? Or the entire crew stranded after damage to their spaceship? On the surface, these would definitely raise the stakes with more lives under threat. However, by leaving it as a single person, the author takes the story in a different direction. Instead of collaboration between crew members, The Martian is, at its heart, a story of one man against a world. In this respect, the drama packs more punch because he has no one else to rely on, and the story is arguably stronger for it.

Heroes

Heroes tend to come in one of two flavours. First, there’s the classic hero, a force for good. The hero may be flawed and imperfect. They’ll be tested, and may be found wanting initially before they are redeemed at the end of the novel. Frodo from The Lord of the Rings is one example: resisting the temptation to take the ring for himself, but coming so very close.

At the other end of the spectrum are anti-heroes, protagonists who might do the right thing, but likely only because it suits them or fits in with their warped moral code. One of the best examples is the titular character from Richard Kadrey’s Sandman Slim, a gladiator escaped from Hell and out for revenge. With a traditional hero, the reader may feel for the hero, their trials and suffering. With an antihero, the reader may sympathise with the hand the protagonist has been dealt, or might just rejoice in the antihero’s reckless abandon and disregard for the rules. Both archetypes have a commonality though: something to draw the reader in and follow the protagonist on their journey. One thing that almost never happens is a successful novel with a protagonist who is almost entirely unlikeable.

However, one exception that comes to mind is Stephen Donaldson’s Chronicles of Thomas Convenant. The original trilogy, beginning with Lord Foul’s Bane, introduced the world to the title character, a thoroughly unpleasant fellow destined to be a hero. He has almost no redeeming qualities, and finding sympathy for Covenant is a constant challenge. It shouldn’t, on the surface, work as a great novel or trilogy. But it does. The trilogy was so successful that a further trilogy followed, and then a final quartet. Explaining why it works is no easy task, but in essence the books work because Donaldson’s writing is so good, compensating for the character deficiencies of the protagonist. Few authors can pull off such a feat, and most don’t try. Heroes and antiheroes don’t have to be black and white, good or evil, and come in many different shades. Trying to write about an unpleasant and unsympathetic protagonist, however, is best avoided.

Omit Needless Words

Strunk and White’s has been around in various forms for over a century and is still valuable today as a guide to style, grammar, and composition. One of the key instructions within is a foundation of concise writing: “Omit needless words.” A simple instruction, but no less important for it. It’s inspired generations of writers, and applies to essays and short stories just as much as novels. In a generation of short attention spans and soundbites, the instruction may be more important than ever. But is there ever a time to break Strunk and White’s writing commandment?

Strunk and White’s has been around in various forms for over a century and is still valuable today as a guide to style, grammar, and composition. One of the key instructions within is a foundation of concise writing: “Omit needless words.” A simple instruction, but no less important for it. It’s inspired generations of writers, and applies to essays and short stories just as much as novels. In a generation of short attention spans and soundbites, the instruction may be more important than ever. But is there ever a time to break Strunk and White’s writing commandment?

By knowing the rules you can effectively break them.

Omitting needless words trims away the fat and forces writers to use the best words rather than the most words; deploying a great metaphor or simile, for example, rather than three average ones. There are, however, a few writers whose novels aren’t famed for brevity and push the limits of whether words are needless or not within their books. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these authors work in Fantasy and Science Fiction, two genres well known for epic works.

Terry Goodkind’s Wizard’s First Rule, the first in his Sword of Truth series, was something different in the Fantasy genre when it came out. As the series and novel titles suggest, there’s a dose of magic and swordplay within the pages. The action, however, is secondary to the story and characters. Goodkind’s novels tend towards slower-paced affairs. Influenced by Ayn Rand and Objectivism, Goodkind’s novels explore morality, power, free will, society, and responsibility to varying degrees, while still being entertaining reads with a dose of swords and magic action. The pacing is often slow, but this is balanced by a richer story world.

Peter F. Hamilton is legendary within Science Fiction for publishing huge novels. They are big in scope and ideas, but also wordy tomes. Space opera is, of course, well suited to big novels and big ideas, and Hamilton brings both to his work. His series are often trilogies, with each volume making a pretty big paperback. The author’s not afraid to spend pages detailing a certain technology like a ship or space station. His work never feels particularly slow, but his novels could be shorter. Perhaps, though, it might also kill some of the charm in his fiction and the style that has made him an international bestseller.

Perhaps the novels of Terry Goodkind and Peter F. Hamilton don’t contain needless words that should be omitted, but their pacing can be quite slow. In the hands of merciless editors, their published novels would be almost unrecognisable. Part of their charm, however, is all those sidesteps and diversions that provide balance to the others elements of each novel. Omitting needless words is a rule every writer should keep in mind. The difficulty, of course, is in recognising which words are truly needless. Working out that is a skill in itself, and one we should all work to hone.

Leave A Comment